The Voyages of Captain James Cook Round the World,

by James Cook, orig. pub. 1777, p.107-128:

At eight o'clock next morning, we steered for Tongataboo [Tongatapu], having a gentle breeze at north-east. About fourteen or fifteen sailing vessels, belonging to the natives, set out with us; but every one of them outran the ships considerably. In the afternoon of the next day we came to an anchor off that island, in a safe station. Soon after I landed, accompanied by Omai [the translator] and some of the officers.

We found the king [Poulaho] waiting for us upon the beach. He immediately conducted us to a small neat house, situated a little within the skirts of the woods, with a fine large area before it. This house, he told me, was at my service during our stay at this island; and a better situation we could not wish for.

We had not been long in the house before a pretty large circle of the natives were assembled before us. A root of the kava plant being brought and laid down before the king, he ordered it to be split into pieces, and distributed to several people of both sexes, who began the operation of chewing it; and a bowl of their favourite liquor was soon prepared.

In the mean time a baked hog and two baskets of baked yams were produced, and afterwards divided into ten portions. These portions were then given to certain people present; but how many were to share in each I could not tell.

The liquor was next served out, but Poulaho seemed to give no directions about it. The first cup was brought to him, which he ordered to be given to one who sat near him. The second was also brought to him, and this he kept. The third was given to me; but their manner of brewing having quenched my thirst, it became Omai's property. The rest of the liquor was distributed to different people by direction of the man who had the management of it.

One of the cups being carried to the king's brother, he retired with this, and with his mess of victuals. Some others also quitted the circle with their portions; and the reason was, they could neither eat nor drink in the royal presence; but there were others present, of a much inferior rank, of both sexes, who did both. Soon after, most of them withdrew, carrying with them what they had not ate of their share of the feast.

I observed, that not a fourth part of the company had tasted either the victuals or the drink; those who partook of the former, I supposed to be of the king's household. The servants who distributed the baked meat and the kava always delivered it out of their hand sitting, not only to the king, but to every other person.

It is worthy of remark, though this was the first time of our landing, and a great many people were present who had never seen us before, yet no one was troublesome, but the greatest good order was preserved throughout the whole assembly.

Before I returned on board, I went in search of a watering-place, and was conducted to some ponds, or rather holes, containing fresh water, as they were pleased to call it. The contents of one of these, indeed, were tolerable; but it was at some distance inland, and the supply to be got from it was very inconsiderable.

Being informed that the little island of Pangimodoo, near which the ships lay, could better furnish this necessary article, I went over to it next morning, and was so fortunate as to find there a small pool that had rather fresher water than any we had met with amongst these islands. The pool being very dirty, I ordered it to be cleaned; and here it was that we watered the ships.

As I intended to make some stay at Tongataboo, we pitched a tent in the forenoon just by the house which Poulaho had assigned for our use. The horses, cattle and sheep, were afterwards landed, and a party of marines, with their officer, stationed there as a guard. The observatory was then set up at a small distance from the other tent; and Mr. King resided on shore, to attend the observations, and to superintend the several operations necessary to be conducted there. For the sails were carried thither, to be repaired; a party was employed in cutting wood for fuel, and plank for the use of the ships; and the gunners of both ships were ordered to remain upon the spot, to conduct the traffic with the natives, who thronged from every part of the island with hogs, yams, cocoa-nuts, and other articles of their produce. In a short time our land-post was like a fair, and the ships were so crowded with visitors that we had hardly room to stir upon the decks.

Feenou [the king's brother] had taken up his residence in our neighbourhood; but he was no longer the leading man. However, we still found him to be a person of consequence; and we had daily proofs of his opulence and liberality, by the continuance of his valuable presents. But the king was equally attentive in this respect; for scarcely a day passed without receiving from him some considerable donation. We now heard, that there were other great men of the island whom we had not as yet seen. Otago and Toobou, in particular, mentioned a person named Mareewagee, who, they said, was of the first consequence in the place, and held in great veneration; nay, if Omai did not misunderstand them, superior even to Poulaho, to whom he was related; but, being old, lived in retirement, and therefore would not visit us. Some of the natives even hinted that he was too great a man to confer that honour upon us. This account exciting my curiosity, I this day mentioned to Poulaho that I was very desirous of waiting upon Mareewagee, and he readily agreed to accompany me to the place of his residence the next morning...

On the 16th, in the morning, after visiting the several works now carrying on ashore, Mr. Gore [John Gore] and I took a walk into the country; in the course of which nothing remarkable appeared, but our having opportunities of seeing the whole process of making cloth [tapa cloth], which is the principal manufacture of these islands, as well as of many others in this ocean. In the narrative of my first voyage, a minute description is given of this operation as performed at Otaheite [Tahiti]; but the process here differing in some particulars, it may be worth while to give the following account of it.

The manufacturers, who are females, take the slender stalks or trunks of the papermulberry [paper mulberry], which they cultivate for that purpose, and which seldom grows more than six or seven feet in height, and about four fingers in thickness. From these they strip the bark, and serape off the outer rind with a muscle-shell [mussel shell].

The bark is then rolled up to take off the convexity which it had round the stalk, and macerated in water for some time (they say a night). After this it is laid across the trunk of a small tree squared, and beaten with a square wooden instrument about a foot long, full of coarse grooves on all sides; but sometimes with one that is plain.

According to the size of the bark, a piece is soon produced; but the operation is often repeated by another hand, or it is folded several times and beat longer, which seems rather intended to close than to divide its texture. When this is sufficiently effected, it is spread out to dry; the pieces being from four to six or more feet in length, and half as broad.

They are then given to another person who joins the pieces, by smearing part of them over with the viscous juice of a berry called to-oo, which serves as a glue. Having been thus lengthened, they are laid over a large piece of wood, with a kind of stamp made of a fibrous substance pretty closely interwoven, placed beneath. They then take a bit of cloth and dip it in a juice expressed from the bark of a tree called kokka, which they rub briskly upon the piece that is making. This at once leaves a dull brown colour, and a dry gloss upon its surface; the stamp, at the same time, making a slight impression, that answers no other purpose that I could see but to make the several pieces that are glued together stick a little more firmly.

In this manner they proceed, joining and staining by degrees, till they produce a piece of cloth of such length and breadth as they want; generally leaving a border of a foot broad at the sides, and longer at the ends, unstained. Throughout the whole, if any parts of the original pieces are too thin, or have holes, which is often the case, they glue spare bits upon them, till they become of an equal thickness.

When they want to produce a black colour, they mix the soot procured from an oily nut called dooedooe, with the juice of the kokka, in different quantities, according to the proposed depth of the tinge. They say that the black sort of cloth, which is commonly most glazed, makes a cold dress, but the other a warm one; and, to obtain strength in both, they are always careful to join the small pieces lengthwise, which makes it impossible to tear the cloth in any direction but one.

On our return from the country we met with Feenou, and took him and another young chief on board to dinner. When our fare was set upon the table, neither of them would eat a bit, saying that they were taboo avy. But, after inquiring how the victuals had been dressed, having found that no avy (water) had been used in cooking a pig and some yams, they both sat down and made a very hearty meal; and, on being assured that there was no water in the wine, they drank of it also.

From this we conjectured that, on some account or another, they were, at this time, forbidden to use water; or, which was more probable, they did not like the water we made use of, it being taken up out of one of their bathing-places. This was not the only time of our meeting with people that were taboo avy; but for what reason we never could tell with any degree of certainty...

The cattle, which we had brought, and which were all on shore, however carefully guarded, I was sensible, ran no small risk, when I considered the thievish disposition of many of the natives, and their dexterity in appropriating to themselves, by stealth, what they saw no prospect of obtaining by fair means. For this reason, I thought it prudent to declare my intention of leaving behind me some of our animals; and even to make a distribution of them previously to my departure.

With this view, in the evening of the 19th, I assembled all the chiefs before our house, and my intended presents to them were marked out. To Poulaho, the king, I gave a young English bull and cow; to Mareewagee, a Cape ram, and two ewes; and to Feenou, a horse and a mare. As my design, to make such a distribution, had been made known the day before, most of the people in the neighbourhood were then present, I instructed Omai to tell them, that there were no such animals within many months' sail of their island; that we had brought them, for their use, from that immense distance, at a vast trouble and expense; that, therefore, they must be careful not to kill any of them till they had multiplied to a numerous race; and, lastly, that they and their children ought to remember, that they had received them from the men of Britane.

He also explained to them their several uses, and what else was necessary for them to know, or rather as far as he knew; for Omai was not very well versed in such things himself. As I intended that the above presents should remain with the other cattle, till we were ready to sail, I desired each of the chiefs to send a man or two to look after their respective animals, along with my people, in order that they might be better acquainted with them, and with the manner of treating them. The king and Feenou did so; but neither Mareewagce, nor any other person for him, took the least notice of the sheep afterwards; nor did old Toobou attend at this meeting, though he was invited, and was in the neighbourhood. I had meant to give him the goats, viz. a ram and two ewes; which, as he was so indifferent about them, I added to the king's share.

It soon appeared, that some were dissatisfied with this allotment of our animals; for early next morning, one of our kids and two turkey-cocks were missing...

In the morning of the 5th, the day of the eclipse, the weather was dark and cloudy, with showers of rain; so that we had little hopes of an observation. About nine o'clock the sun broke out at intervals for about half an hour; after which it was totally obscured till within a minute or two of the beginning of the eclipse.

We were all at our telescopes, viz. Mr. Bayly, Mr. King, Captain Clerke [Charles Clerke], Mr. Bligh [William Bligh], and myself. I lost the observation by not having a dark glass at hand, suitable to the clouds that were continually passing over the sun; and Mr. Bligh had not got the sun into the field of his telescope; so that the commencement of the eclipse was only observed by the other three gentlemen, and by them with an uncertainty of several seconds, as follows:—

| | | H. | M. | S. | |

| By | By Mr. Bayly, at . . . . . . | 11 | 46 | 23½ | Apparent time. |

| | Mr. King, at . . . . . . | 11 | 46 | 28 | Apparent time. |

| | Capt. Clerke, at . . . . . . | 11 | 47 | 5 | Apparent time. |

Mr. Bayly and Mr. King observed with the achromatic telescopes, belonging to the Board of Longitude, of equal magnifying powers; and Captain Clerke observed with one of the reflectors. The sun appeared at intervals, till about the middle of the eclipse; after which it was seen no more during the day; so that the end could not be observed. The disappointment was of little consequence, since the longitude was more than sufficiently determined, independently of this eclipse, by lunar observations, which will be mentioned hereafter.

As soon as we knew the eclipse to be over, we packed up the instruments, took down the observatories, and sent everything on board that had not been already removed. As none of the natives had taken the least notice or care of the three sheep allotted to Mareewagee, I ordered them to be carried back to the ships.

I was apprehensive that, if I had left them here, they ran great risk of being destroyed by dogs. That animal did not exist upon this island, when I first visited it in 1773; but I now found they had got a good many, partly from the breed then left by myself, and partly from some imported, since that time, from an island not very remote, called Feejee [Fiji].

The dogs, however, at present, had not found their way into any of the Friendly Islands, except Tongataboo; and none but the chiefs there had as yet got possession of any...

|

| | |

See also:

Papua New Guinea News - Fiji - Samoa

New Caledonia - Australia - New Zealand

|

|

All of Tonga is

one time zone at GMT+13,

with no Daylight Savings time.

|

Tonga News

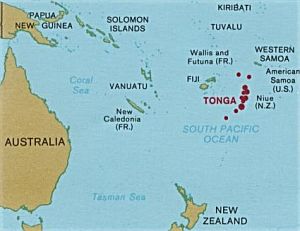

The first humans arrived in Tonga around 1000 B.C. The islands’ politics were probably highly centralized under the Tu’i Tonga, or Tongan king, by A.D. 950, and by 1200, the Tu’i Tonga had expanded his influence throughout Polynesia and into Melanesia and Micronesia. The Tongan Empire began to decline in the 1300s, descending into civil wars, a military defeat to Samoa, and internal political strife that saw successive leaders assassinated. By the mid-1500s, some Tu’i Tongans were ethnic Samoan and day-to-day administration of Tonga was transferred to a new position occupied by ethnic Tongans.

Dutch sailors explored the islands in the 1600s and British Captain James COOK visited Tonga three times in the 1770s, naming them the Friendly Islands for the positive reception he thought he received, even though the Tongans he encountered were plotting ways to kill him.

In 1799, Tonga fell into a new round of civil wars over succession. Wesleyan missionaries arrived in 1822, quickly converting the population. In the 1830s, a low-ranking chief from Ha’apai began to consolidate control over the islands and won the support of the missionaries by declaring that he would dedicate Tonga to God. The chief soon made alliances with leaders on most of the other islands and was crowned King George TUPOU I in 1845, establishing the only still-extant Polynesian monarchy.

TUPOU I declared Tonga a constitutional monarchy in 1875 and his successor, King George TUPOU II, agreed to enter a protectorate agreement with the UK in 1900 after rival Tongan chiefs tried to overthrow him. As a protectorate, Tonga never completely lost its indigenous governance, but it did become more isolated and the social hierarchy became more stratified between a group of nobles and a large class of commoners. Today, about one third of parliamentary seats are reserved for nobles.

Queen Salote TUPOU III negotiated the end of the protectorate in 1965, which was achieved under King TUPOU IV, who in 1970 withdrew from the protectorate and joined the Commonwealth of Nations.

A prodemocracy movement gained steam in the early 2000s, led by future Prime Minister ‘Akilisi POHIVA, and in 2006, riots broke out in Nuku’alofa to protest the lack of progress on prodemocracy legislation. To appease the activists, in 2008, King George TUPOU V announced he was relinquishing most of his powers leading up to parliamentary elections in 2010; he died in 2012 and was succeeded by his brother ‘Aho’eitu TUPOU VI.

Tropical Cyclone Gita, the strongest-ever recorded storm to impact Tonga, hit the islands in February 2018 causing extensive damage.

CIA World Factbook: Tonga

Area of Tonga:

748 sq km

4x the size of Washington, DC

Population of Tonga:

105,221 (2023) | 120,898 (2009)

Languages of Tonga:

Tongan, English

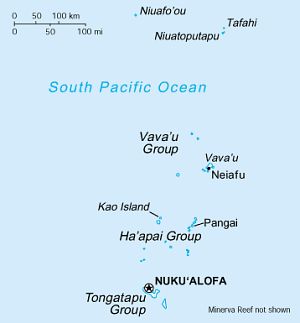

Tonga Capital:

Nuku'alofa

NUKU'ALOFA WEATHER

Free Books on Tonga (.pdfs)

...Natives of the Tonga Islands v1 Mariner 1827

...Natives of the Tonga Islands v2 Mariner 1827

Fiji and the Friendly Isles Scholes 1882

Tonga and the Friendly Islands Farmer 1855

The Tonga Islands... Adams 1890

Online Book Search Engines

Tonga Reference Articles and Links

Wikipedia: Tonga - History of Tonga

BBC Country Profile: Tonga

US State Department: Tonga Profile

Australia & Pacific Maps

WikiTravel: Tonga

Tonga News Websites

Tonga Broadcasting Commission

Matangi Tonga Online

ABYZ: Tonga News Links

Moon Handbooks: Tonga-Samoa (1999)

|