Narrative of a Year's Journey Through Central and Eastern Arabia,

1866, by William Gifford Palgrave, v2 p. 230-243:

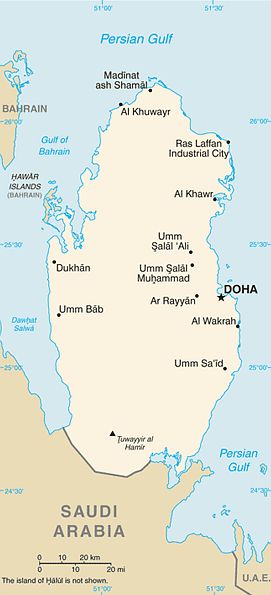

"On we swept," and passed many a shoal and reef, just perceptible by a change of colour upon the face of the water or a long treacherous ripple; to our right was the coast of Bahreyn [Bahrain], its sandy monotony broken here and there by some small and dingy village. Near nightfall we sighted the western corner of Katar [Qatar], called in many maps Bahran, but on what authority I hardly know; certainly no one here ever gives it that name. Now "Bahran" is simply the nominative of which "Bahreyn" is the genitive or objective case; and hence I suspect that our geographers may have been led astray by some grammatical misapprehension of a phrase. The coast of Katar before us looked rocky, but not high; it is very desolate-seeming; at intervals rise small watch-towers, much like those seen on different points of the Syrian shore, and ascribed by popular tradition to the Empress Helena, wife of [Constantius Chlorus, and mother of] Constantine the Great.

During the night we were startled from slumber by the grinding of our keel upon a reef, an event followed by so much confusion, shouting, and awkward unseamanship, that our getting off was more the work of lucky chance than of the crew. Next day we had to endure foul wind and drizzling rain with nothing to shelter us, while we slowly worked our way up under Ras Rekan [Ra's Rakan, Ras Rakhan], the northernmost cape of the Katar promontory; a somewhat bold headland girt with cliffs thirty or forty feet high; we were long in getting round it. I noticed a good-sized fort on the heights; it belongs to a village situated in a gorge close by, but I have forgotten the name [Al Zubarah or Az Zubarah].

By the morning of the 28th [of January, 1863] we had fairly rounded Rekan, and drove southwards before the gale for Bedaa' [Al Bida, which was later engulfed by Doha]. The line of coast was all along steep, but of inconsiderable height; five or six villages, the abodes of fishermen, intervene between the cape and Bedaa', opposite which we arrived towards evening. Ebn-Khamees went on shore to pay his compliments to the chief and prepare a lodging; but the hour was late, and I preferred remaining on board the night. Next morning my companion returned to fetch me, and we waded together across a wide sandy reach till we entered Bedaa', the principal town of Katar at the present day.

It is the miserable capital of a miserable province. To have an idea of Katar, my readers must figure to themselves miles on miles of low barren hills, bleak and sun-scorched, with hardly a single tree to vary their dry monotonous outline; below these a muddy beach extends for a quarter of a mile seawards in slimy quicksands, bordered by a rim of sludge and seaweed. If we look landwards beyond the hills, we see what by extreme courtesy may be called pasture land, dreary downs with twenty pebbles for every blade of grass; and over this melancholy ground scene, but few and far between, little clusters of wretched, most wretched, earth cottages and palmleaf huts, narrow, ugly, and low; these are the villages, or rather the "towns" (for so the inhabitants style them), of Katar.

Yet poor and naked as is the land, it has evidently something still poorer and nakeder behind it, something in short even more devoid of resources than the coast itself, and the inhabitants of which seek here by violence what they cannot find at home. For the villages of Katar are each and all carefully walled in, while the downs beyond are lined with towers, and here and there a castle "huge and square" makes with its little windows and narrow portals a display of strength hardly less, so it might seem, superfluous than the Tower of London in the nineteenth century. But these castles are in reality by no means superfluous, for Katar has wealth in plenty, and there are robbers against whom that wealth must be guarded.

Whence comes this wealth amid so much apparent poverty, and in what does it consist? What I have just described is, so to speak, nothing but the heaps of rubbish and the rubbishy miners' huts about the shaft's month; close by is the mine itself, a rich and never-failing store. This mine is no other than the sea, no less kindly a neighbour to the inhabitants of Katar than their dry land is a niggard host.

In this bay are tbe best, the most copious pearl-fisheries of the Persian Gulf, and in addition an abundance almost beyond belief of whatever other gifts the sea can offer or bring. It is from the sea accordingly, not from the land, that the natives of Katar subsist, and it is also mainly on the sea that they dwell, passing amid its waters the one half of the year in search of pearls, the other half in fishery or trade.

Hence their real homes are the countless boats which stud the placid pool, or stand drawn up in long black lines on the shore; while little care is taken to ornament their land houses, the abodes of their wives and children at most, and the unsightly strong-boxes of their gathered treasures.

"We are all from the highest to the lowest slaves of one master, Pearl," said to me one evening Mohammed-ebn-Thanee [Muhammad bin Thani, 1800—1878], chief of Bedaa'; nor was the expression out of place. All thought, all conversation, all employment, turns on that one subject; everything else is mere by-game, and below even secondary consideration.

I mentioned robbers and the danger of pillage. From each other, indeed, the men of Katar have, it seems, little to fear. Too busy to be warlike, they live in a passive harmony which almost dispenses with the ordinary machinery of government itself. Ebn-Thanee, the governor of Bedaa', is indeed generally acknowledged for head of the entire province, which is itself dependant on the Sultan of 'Oman; yet the Bedaa' resident has in matter of fact very little authority over the other villages, where everyone settles his affairs with his own local chief, and Ebn-Thanee is for those around only a sort of collector-in-chief, or general revenue-gatherer, whose occupation is to look after and to bring in the annual tribute on the pearl fishery [Qatar was controlled by Bahrain from the 1850s to 1868, and paid tribute to Bahrain until 1872].

Mohammed-el-Khaleefah [Muhammad ibn Khalifah Al Khalifa of Bahrain] has also a sort of control or presidential authority in Katar, but its only exercise in the hands of this worthy seems to be that of choosing now and then a pretty girl (for the female beauty of 'Oman extends itself, though in an inferior degree, to Katar), on whom to bestow the brief honours of matrimony for a fortnight or a month at furthest, with a retiring pension afterwards. While I was myself at Bedaa' the uxorious Khaleefah paid a visit to the neighbouring town of Dowhah, and there lightly espoused a fair sea-nymph of the place, to he no less lightly divorced long before my return from 'Oman. No solemnity was spared on the occasion; jurists were consulted, the dowry paid, public rejoicings were ordered, and public laughter came unbidden; while Mohammed wasted the hard-gained wealth of Menamah [Manamah, capital of Bahrain] and Moharrek [Al-Muharraq, 2nd largest city in Bahrain] in the pomp of open vice.

Zabarah, the largest of the island towns, indeed the only one of any territorial importance, is the residence of one of the El Khaleefahs ; but it does not therefore claim any particular preeminence over the remaining localities of the province.

But if the people of Katar have peace within, they are exposed on the land side to continual marauding inroads from their Bedouin neighbours, the Menaseer and Aal-Morrah [Al-Murrah]. The former of these tribes is numerous and warlike, and their favourite range of rapine or pasture extends from the frontiers of Hasa [Al-Hasa] to those of 'Oman proper near Sharjah. Few nomad clans give more annoyance to the inhabited districts, and few, if accounts be correct, have amassed a greater amount of ill-gotten opulence from plunder and bloodshed.

These marauders possess large droves of camels and flocks of sheep, acquired and augmented at the expense of the villagers; and from the barren desert hard by, their retreat when pressed by danger, they bring their animals to pasture on the narrow strip of upland that lies between the coast-hills and the Dahnii. Hence the necessity for the towers of refuge which line the uplands: they are small circular buildings from twenty-five to thirty feet in height, each with a door about half-way up the side and a rope hanging out; by this compendious ladder the Katar shepherds, when scared by a sudden attack, clamber up for safety into the interior of the tower, and once there draw in the rope after them, thus securing their own lives and persons at any rate, whatever may become of their cattle. For to scale a wall fifteen feet high is an exploit beyond the ingenuity of the most skilful Bedouin. At times the Menaseer, emboldened by impunity (for the people of Katar have no great pretensions to warlike valour), attack the main villages, and carry off more valuable booty than kine [cattle] and sheep. Hence the origin of the strongholds or keeps within the towns themselves, and of the walls which surround them.

Further down the coast towards the east begin the settlements of Benoo-Yass, an ill-famed clan, half Bedouins, half villagers, and all pirates; the very same whose cruisers have in former times given to this district the ominous name of "Pirate coast." The head point or main centre of Benoo-Yass is Soor; it is, so I was informed, a mere aggregation of huts, clustered under some old and ruined fortresses, dens of the robbers. The Benoo-Yass belong to the original inhabitants of 'Oman, and though devoid of its civilization, partake in its political and national feelings; hence they are not only haters of all Muslims and Wahhabees [Wahhabis], but even fierce enemies and aggressors whenever occasion permits.

When plunder is the order of the day, they readily join hands with the Menaseer, though widely different from them in origin and in appearance. For the Menaseer, judging by tradition, physical outline, and dialect, are a branch of the great 'Abs family [Banu Abs], of whom was the famous 'Antarah-ebn-Sheddad [Antarah ibn Shaddad], and are, accordingly, by race Nejdeans from Keys-'Eylan, while Benoo-Yass trace their origin to the Kahtanee [Qahtanite] family of Modhej, and travelled hither northwards from Hadramaut, so runs their tale.

Profit, however, like misery, may unite strange bedfellows. Both the Menaseer and Benoo-Yass have been much repressed of late by the activity of Ahmed-es-Sedeyree, the Nejdean resident at Bereymah [Dahiyah, Oman] (the same whose brother 'Abd-el-Mahsin-es-Sedeyree entertained us at Mejmaa'); while at sea the red 'Omanee pennon of the pirates has grown pale before the redder cross of St. George; and none but pearl-oysters and fishes have any violence to fear in this bight of the Persian Gulf at the present day.

Of the third great clan hereabouts, namely, Afd-Morrah, the tenants of the Dahna [Ad-Dahna Desert] itself, and still more numerous and widespread, though luckily less pugnacious, than the Menaseer, I have already made mention. The Bedouins of this tribe, who visit Katar and 'Oman, now for trade and now for plunder, do not acknowledge Wahhabee sovereignty, but are, after their irregular fashion, some of them tributaries to the Sultan of Oman, while some remain at the bidding and buying of subordinate land-chiefs.

The climate of Katar is remarkably dry; under the arid breath of the encroaching desert, the sea-air only a few miles inland seems to lose all trace of humidity. The soil is poor, gravel and marl mixed with sand; occasional springs of water supply wells laboriously pierced through the encrusted upper strata. The gardens are small and unproductive, nor did I see any cornfields or date-groves worthy of the name. The air too is said to be unhealthy; perhaps the rotting pools of stagnant sea-water that border all the coast, are the cause of this.

Such is the general outline of Katar. On landing at Bedaa' we went right to the castle, a donjon-keep, with outhouses at its foot, offering more accommodation for goods than for men.

Under a mat-spread and mat-hung shed within the court sat the chief, Mohammed-ebn-Thanee, a shrewd wary old man, slightly corpulent, and renowned for prudence and good-humoured easiness of demeanour, but close-fisted and a hard customer at a bargain; altogether, he had much more the air of a businesslike avaricious pearl-merchant (and such he really is), than of an Arab ruler. Bound him were placed many sallow-featured individuals, their skins soddened by frequent sea-diving, and their faces wrinkled into computations and accounts. However, Ebn-Thanee, though eminently a "practical " man, had thus far put his sedentary habits to intellectual profit, that by dint of study he had rendered himself a tolerable proficient in literary and poetical knowledge, and took great pleasure in discussing topics of this nature. Nay, he even pretended to have some medical skill, and did I think really possess about the same amount of it that many an old woman may boast of in a country village of Lancashire or Essex. Besides, he liked a joke, and could give and take one with a good grace.

|

| | |

see also: Saudia Arabia News - Iraq - Iran

Kuwait - Bahrein - UAE - Oman

|

|

All of Qatar

is one time zone

at GMT+3 with no DST

|

Qatar News

Ruled by the Al Thani family since the mid-1800s, Qatar within the last 60 years transformed itself from a poor British protectorate noted mainly for pearling into an independent state with significant hydrocarbon revenues.

Former Amir HAMAD bin Khalifa Al Thani, who overthrew his father in a bloodless coup in 1995, ushered in wide-sweeping political and media reforms, unprecedented economic investment, and a growing Qatari regional leadership role, in part through the creation of the pan-Arab satellite news network Al-Jazeera and Qatar's mediation of some regional conflicts.

In the 2000s, Qatar resolved its longstanding border disputes with both Bahrain and Saudi Arabia and by 2007, Doha had attained the highest per capita income in the world. Qatar did not experience domestic unrest or violence like that seen in other Near Eastern and North African countries in 2011, due in part to its immense wealth and patronage network.

In mid-2013, HAMAD peacefully abdicated, transferring power to his son, the current Amir TAMIM bin Hamad. TAMIM is popular with the Qatari public, for his role in shepherding the country through an economic embargo by some other regional countries, for his efforts to improve the country's healthcare and education systems, and for his expansion of the country's infrastructure in anticipation of Doha's hosting international sporting events. Qatar became the first country in the Arab world to host the FIFA Menís World Cup in 2022.

Following the outbreak of regional unrest in 2011, Doha prided itself on its support for many popular revolutions, particularly in Libya and Syria. This stance was to the detriment of Qatarís relations with Bahrain, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which temporarily recalled their respective ambassadors from Doha in March 2014.

TAMIM later oversaw a warming of Qatarís relations with Bahrain, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE in November 2014 following Kuwaiti mediation and signing of the Riyadh Agreement. This reconciliation, however, was short-lived.

In June 2017, Bahrain, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE (the "Quartet") cut diplomatic and economic ties with Qatar in response to alleged violations of the agreement, among other complaints. They restored ties in January 2021 after signing a declaration at the Gulf Cooperation Council Summit in Al Ula, Saudi Arabia.

In 2022, the United States designated Qatar as a major non-NATO ally.

CIA World Factbook: Qatar

Area of Qatar:

11,437 sq km

slightly smaller than Connecticut

Population of Qatar:

2,532,104 (2023) | 840,926 (2010)

Languages of Qatar:

Arabic official, English

Qatar Capital:

Doha

DOHA WEATHER

Free Books on Qatar (.pdfs)

Through Central & Eastern Arabia v2 Palgrave 1866

Online Book Search Engines

Qatar Reference Articles and Links

Wikipedia: Qatar - History of Qatar

BBC Country Profile: Qatar

US State Department: Qatar Profile

Maps of Qatar

WikiTravel: Qatar

OPEC Org. of Petroleum Exporting Countries

Qatar News Websites

Al Jazeera

Gulf Times

The Peninsula

Qatar Tribune

ABYZ: Qatar News Links

|